|

Parisian Sanitation from 1200-1789

12th century Paris, still confined to the Isle de la Cite, used the Seine to clean

the city. In the 11th and 12th centuries, public baths were plentiful in Paris;

however, the presence of naked men and women together brought

strong disapproval from the Church.

Public bathhouses became very

rare and did not reappear until the 19th century.

This negative attitude

in regards the body - the embodiment of sin - and proper hygiene

was believed to benefit the soul. Constant water shortages did not

help matters much. Paris's chronic lack of potable water caused

outbreaks of water-borne diseases well into the 18th Century,

since water was available from only a few fountains and wells, and

the addition of new water supplies could barely keep up with demand

of a growing population.

Paris in the 13th century transformed itself from feudal estates to those the

church and state, with land and power divided equally. Phillipe

Augustus begins public works such as the Cimetiere des Saints Innocents

and the masonry fortification around Paris to relieve congestion. He also

ordered the paving of the roads in order to cut down on the offensive stench

of the impregnated mud. This cuts down on the mud, which still remains

considerable, but also creates the need to get rid of garbage and sewage,

which could no longer be assimilated back into the ground.

The long periods of war from the 14th to the 17th century limited the

physical expansion of Paris to its fortifications. The influx of peasants

seeking better fortune formed a constant source of population increases

since the number of deaths in Paris almost always outpaced the number of

births. The accumulation of refuse in the streets reached the point that

in 1348 Phillipe VI de Valois passed an ordinance requiring the citizens

to sweep in front of their doors and to transport their garbage to dumps

or risk fines and imprisonment. He established the first corp of sanitation

workers to clean the streets. Even with ordinances issued every few years,

these brought little relief and were difficult to enforce. Garbage piled up in

the streets, making some completely inaccessible. Finally in desperation,

the King made Nobility set an example, and people began to follow

the orders, (but now they dumped their waste on public property and

out of the way places.)

In the 16th century, the plagues, brought by rats, were ravaging most

European cities and brought new sanitation ordinances. In 1539, Francois I

orders property owners to build cesspools, for the collection of human

sewage, into each new dwelling. Those who would not comply have their

houses confiscated, and rents were collected to pay for the cesspools. Most

of these cesspools were built to leak so as to be emptied less frequently

--water tightness was not mandated until the 19th century. Cesspools

remained the most common method of dealing with human sewage until

the late 19th century and cut down on the human sewage found on the street.

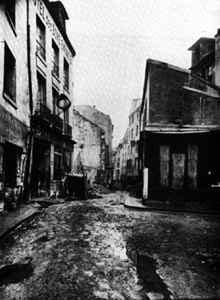

Eugene Atget The Rue St Medard in the 5th Arrondissement @1900

Eugene Atget @ 1900, 50 Rue des Rennes

in the 6th Arrondissement,

an older type of street with no raised sidewalks

and a central open gully for sewerage.

In 1674, a decree states that feces must be separated from other wastes at the

dump, in order to begin manufacturing poudrette or human guano--a greasy,

powdery, flammable substance made by open-air fermentation of human

sewage. Valued as a fertilizer, it was toxic to breathe and incredibly foul

smelling for miles around.

An ordinance of 1721 stated that property owners must pay for the cleaning

of the covered sewers that pass under their building. The property owners

concluded from this that they had the right to dump all their refuse in the

sewer, aggravating the problem and causing many to become blocked.

Another ordinance was passed in 1736 stating those found dumping in

covered sewers would be heavily fined, and corporal punishment would be

administered to the servants. A similar ordinance was once again passed 1755

to no avail, and illegal dumping continued.

An ordinance of 1780 once again forbade people from throwing water,

urine, feces or household garbage out the window.

|